Hidden stories #8

31 August 2025

A look into the collection

The Driessen Collection, consisting of almost seventy handwritten manuscripts containing samples from the ‘Leidse Katoenmaatschappij’ (Leiden Cotton Company), once formed the starting point of the TextielMuseum. This oldest museum collection is a valuable and vast resource, but also inextricably linked to a global chain of power and inequality. In this blog, curator-in-training Sidda van Putten talks about the LKM's cotton trade and why it is crucial to keep revisiting this collection in the context of colonialism.

From the exhibition Makers on materials (2024), photograph by Geisje van der Linden

The cotton of the Driessen collection

In 1954, the municipality of Tilburg laid the foundation for the TextielMuseum's collection. It did so by acquiring the extraordinary textile collection of the Driessen family, owners of the Leidsche Katoenmaatschappij (LKM). The collection consisted of fabrics, books and pictures, forming the first foundation of the museum, even before a building existed. In recent years, much of this heritage has been researched, digitized and made accessible to the public.

Librarian Jantiene van Elk previously wrote a blog about it, arguing for a global history of cotton printing in Europe. Textile researcher Sabine Bolk also published an extensive article on Things That Talk about the LKM's fake batik. Their work shows the importance of understanding the context of this collection: where the patterns came from, what meanings the fabrics carried and how the Leiden Cotton Company appropriated these patterns.

Building on this discourse, I dove into the archives myself, looking for more information on the origins of the most basic element of cotton printing: the cotton itself.

Decolonizing is revealing

Thierry Oussou, White Gold |||, photograph by Josefina Eikenaar - Textile Museum

Cotton is a material with many memories. The 'white gold' was the engine of the industrial revolution and driving force of world trade. But it also brought with it, centuries of exploitation.

From enslaved people, to populations driven off their land to make room - cultivation was always linked to violence and inequality. In the process, land was depleted by intensive production. The economic and logistic structures laid in the nineteenth century still function. Even today, people in the global south are exploited, so that in the Netherlands a T-shirt can retail for 15 euros.

Literary scholar and decolonial thinker Rolando Vázquez Melken argues that decolonization means: making visible the realities that have been erased by 'modernity'.

This is precisely why it is important to re-examine collections like those of the LKM. They are not only heritage, but also tangible witnesses to the rise of a colonial and capitalist world order. The system that made the European cotton industry great, operates to this day.

The extensive Driessen collection, held by the TextielMuseum, could not have existed without the capital the Driessen family built up with their cotton trade. But who paid the price for this? Where did they buy their cotton, and by whom was it picked?

Besides this historical research, the Driessen collection is also artistically studied. Artists Ratri Notosudirdjo, AYO and Sandim Mendes critically examine the collection. The resulting insights are the starting point for developing new work in the TextielLab. The works will be presented in an exhibition, taking place at the museum in 2026.

A search in old books

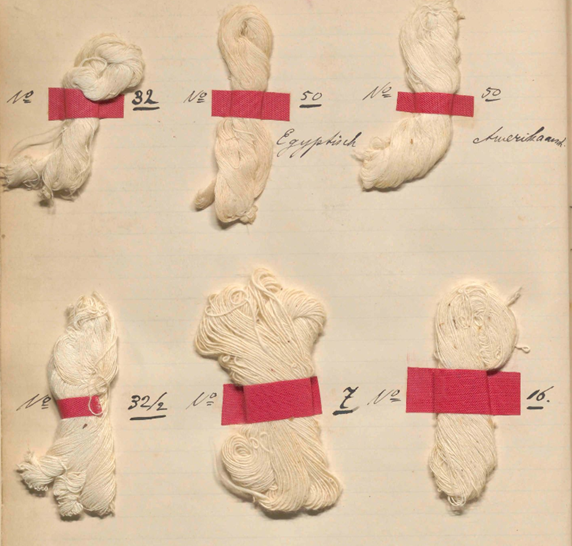

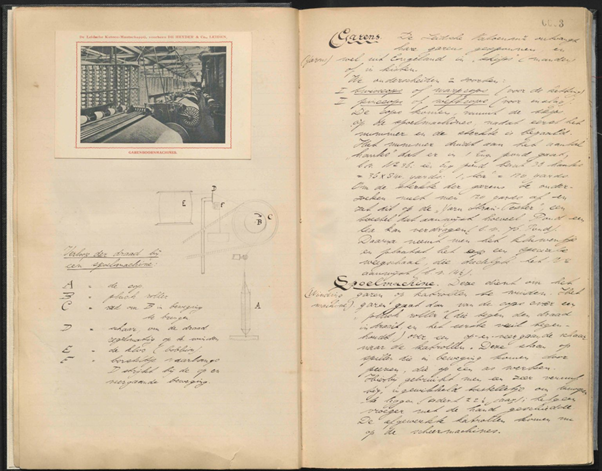

Cotton samples from the description of the LKM weaving mill in 1907

The trail started close to home, in the TextielMuseum's own collection. Thanks to the digitization of recipe books - a project of volunteers and librarian Van Elk - I was able to do a more targeted search.

In the book ‘Fabrikage van katoen,’ Louis Driessen describes the production process in detail:

"The Leidsche Katoenmaatschappij receives its yarns spun, from England in skips (baskets) or in boxes. We distinguish two types:

I. Swisscops or warpcops (for the warp)

II. Pinccops or weftcops (for weft)."

Description of the LKM weaving mill in 1907

That fact led me to the invoice books of the LKM, kept in Erfgoed Leiden en Omstreken (ELO). Old, almost illegible books full of handwritten data. And so, a trading network slowly loomed up.

Manchester as a hub

Most of the names in the invoices referred to trading houses in Manchester, the heart of the British cotton industry. Although, many sources from British archives have been digitized, I could not find all the names in the invoice book. Thanks to help from researchers in nineteenth-century industry in Manchester, I was eventually able to identify a number of main suppliers who supplied spun cotton to the LKM. Such as J.S. Gaunt, a cotton merchant active in Manchester and Nottingham. The name S.D. Bles also pops up regularly, probably referring to the trading house S.D. Bles and Sons. They supplied yarn to Leiden, but where did they get their cotton from?

Until 1861, most of Manchester's cotton came from the southern United States, produced by enslaved people and shipped via the port of Liverpool.

The American Civil War brought a break. When supplies stopped, traders sought refuge in Egypt, India and the Ottoman Empire. It is likely that the LKM's cotton also followed these new routes.

More data are needed to prove this: import books of Manchester trading houses, ship lists, customs records. They could reveal from which plantations, ports and regions the Leiden cotton came.

What we don’t know

The investigation is still in its early stages. The LKM's invoice books provide a glimpse, but not the full story. They show who the British suppliers where, but remain silent about the origin of the bales of cotton.

In Great Britain, a great deal of research has been done into the origin of cotton. In 2023, The Guardian traced the plantations in which the newspaper's founders invested, including the names of enslaved people who worked there. Their research began with exactly the same sources: invoices and trade registers.

A similar project on the LKM would reveal a forgotten history – from plantation to factory, from the people who picked the cotton to the fabrics that can be admired today in books in Tilburg.

A trail that continues

The Driessen collection at the TextielMuseum is rich and multifaceted. But it is also inextricably linked to a global chain of labor, power and inequality.

The invoice books have exposed the tail end of that chain. The important thing now, is to keep asking questions, not because there is a guarantee of an answer, but because they force us to move.